What? BantUGent research seminar

When? March 23, 2022, 2pm

Where?

Simon Stevin Room, Plateau-Rozier, Jozef Plateaustraat 22, 9000 Ghent (online through

Zoom, passcode: KG14YtTh)

Angi Ngumbu (The Seed Company) visits BantUGent on Wednesday March 23 and will give a talk titled “Applied Linguistics: Stories of how linguistics is impacting the lives of the speakers of minority languages in DRC”

Angi Ngumbu has been working as a linguist and project manager in the two Congos (Brazzaville and Kinshasa) for 15 years. She will share about the different projects she has worked on during this time in applied linguistics, from picture dictionaries, language documentation, survey, and orthography development. Some of this work has been directly influenced by or done in collaboration with personnel from Ghent University.

Venue: Simon Stevin Room

Contact: koen.bostoen@ugent.be

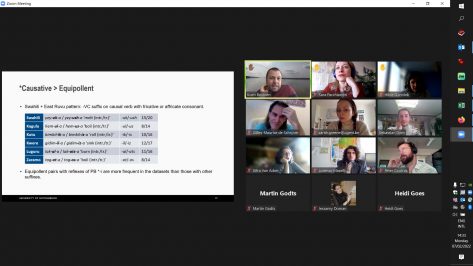

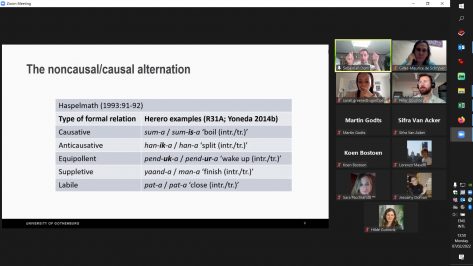

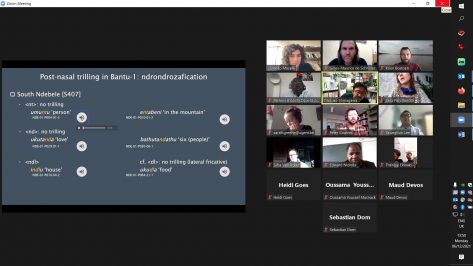

On April 1, 2022 (9.30 am CET), Heidi Goes (BantUGent) defends her PhD dissertation titled “A historical-comparative approach to phonological and morphological variation in the Kikongo Language Cluster, with a special focus on Cabinda”, which she wrote under the co-supervision of Prof. Koen Bostoen (BantUGent) and Prof. Gilles-Maurice de Schryver (BantUGent). The jury members are Prof. Bruce Connell (York University), Prof. Nobuko Yoneda (Osaka University), Prof. Joseph Koni Muluwa (ISP Kikwit), Prof. Mark Janse (UGent) and Dr. Guy Kouarata (UGent). The president of the jury is Prof. Jo Van Steenbergen (UGent) and the secretary Dr. Hilde Gunnink (UGent).

This event can also be followed online through MS Teams. More info: heidi.goes@ugent.be

The ceremony will be followed by a reception (near the Faculty Council, Blandijnberg 2, first floor)

Please confirm your presence using this link (https://webappsx.ugent.be/eventManager/events/cabinda), at the latest Wednesday at noon (23/3/2022).

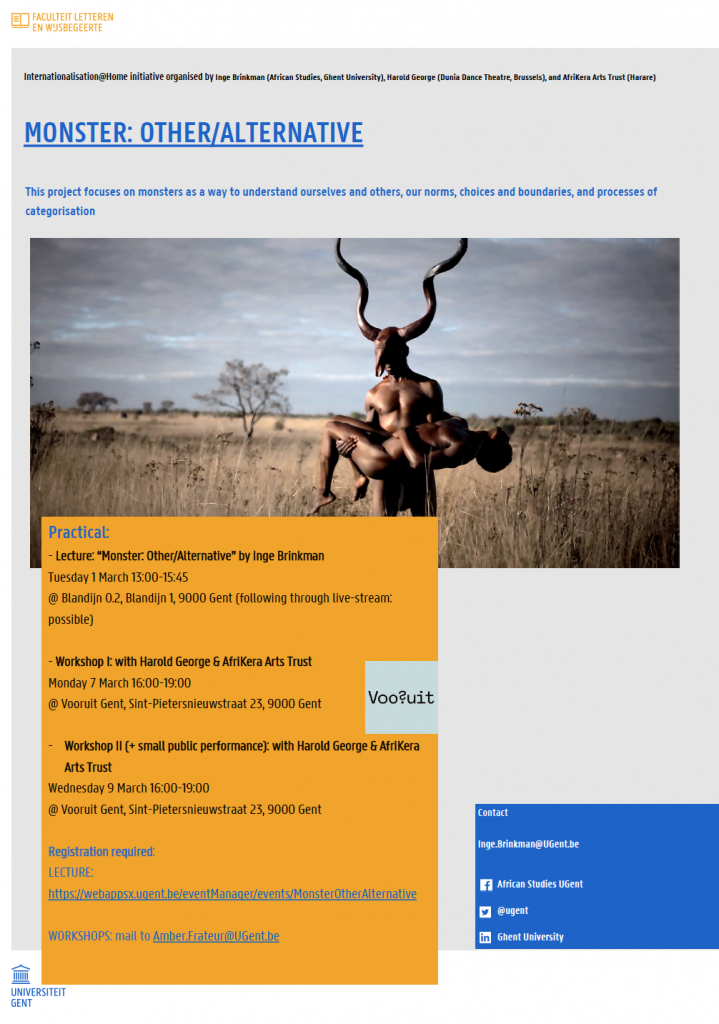

2 Workshops with choreographer Harold George in de Vooruit. Contact Amber.Frateur@UGent.befor information

A dance rehearsal/debate: with Harold George, Dunia Dance Theatre & AfriKeraArts

Registration:https://webappsx.ugent.be/eventManager/events/DANCEREHEARSAL

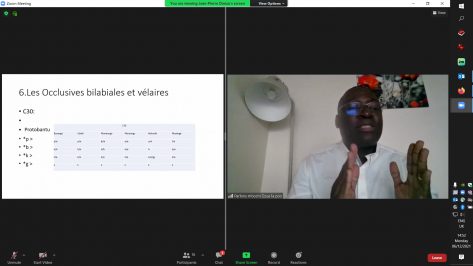

The Bantu languages are the largest African language family, both in terms of number of languages and speakers and geographical distribution. About 350 million or about one in three Africans speak one or more of the 500 or so Bantu languages, which stretch from above the equator to South Africa. Swahili, Lingala, Kongo, Luba, Rwanda, Rundi, Ganda, Zulu, Xhosa, and Shona are just some of the best-known Bantu languages. Proto-Bantu is about 5000 years old and is said to have been born in the border area between Nigeria and Cameroon. This lecture is about the reconstruction of this hypothetical ancestral language, about the exceptionally rapid and large-scale diffusion of its daughter languages and about the history and future of the study area.

https://www.historischetalen.be/cursus/twaalf-smaakmakers/